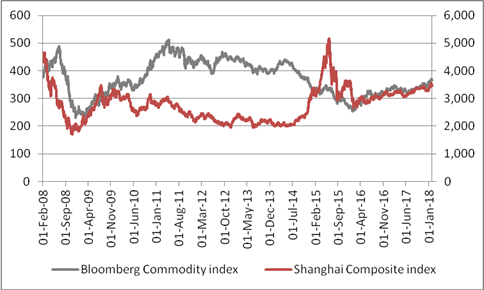

“Whether they have direct exposure to China or Chinese companies, or indirect exposure via companies which operate there, investors will need to keep an eye on the Middle Kingdom in 2018 as it has the potential to influence a range of asset classes - note how the Bloomberg Commodity index seems to take its lead from market and economic events in China.

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream

The good news

“GDP growth of 6.9% exceeded Party targets and consensus forecasts in 2017. The International Monetary Fund expects further strong progress in 2018 and 2019 and does not seem unduly concerned by prospects of a ‘hard landing,’ whereby China slows very suddenly.

“A surge in the currency, the renminbi, also speaks of economic health. Global markets panicked in summer 2015 and early 2016 amid fears that China would try to devalue its way out of a growth slowdown and export price cuts and deflation around the world.

The bad news

“At barely 20% of GDP, China’s government debts are low, especially compared to the West, but it is running an annual budget deficit and its borrowings are rising. In addition, a lot of debt sits between the Government and the private sector within the State Owned Enterprises, while the Party is clearly becoming concerned about the extent of the private sector’s liabilities, too. Data from the China Banking Regulatory Commission show that total bank assets had reached $38 trillion by the end of 2017 – up from just $6 trillion a decade ago.

“That sort of growth can’t come without a few sour loans and some poor capital allocation along the way and this in turn may prompt the doubters to question just how long China can continue to prime the economic pump with a combination of fiscal and monetary stimulus. Growth in 2017 did seem to rely heavily on old, industrial China, rather than the one beloved of bulls of China, which is booming owing to the rise of the middle class, increased consumption, technological advances and the rise of web-services giants such as Baidu, Tencent and Alibaba.

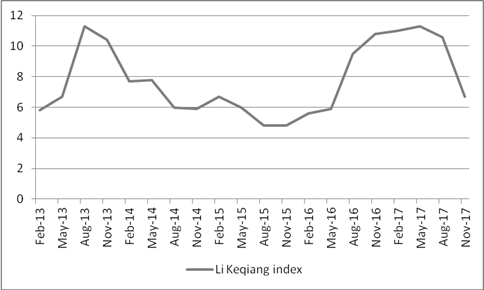

“This is because the so-called Li Keqiang index made a comeback last year, only to lose momentum toward the end of the year. The indicator is based on the three economic indicators which the Prime Minister is believed to follow in preference to official Government statistics, namely demand for loans, rail cargo traffic volumes and electricity consumption.

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream

Three indicators to watch

“Besides GDP growth, Government policy and the Li Keqiang index, investors might like to watch for three particular indicators which may tell them whether China’s influence on global financial markets in the Year of the Dog could be benign or malign:

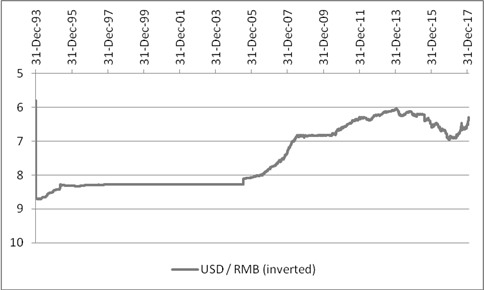

“The currency. Renewed weakness in the renminbi could be a source of concern for markets. This is because of the precedent offered by the 1994 devaluation which, accompanied by a sharp tightening of monetary policy by the US Federal Reserve, caused chaos in global stock, bond and currency markets alike.

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream

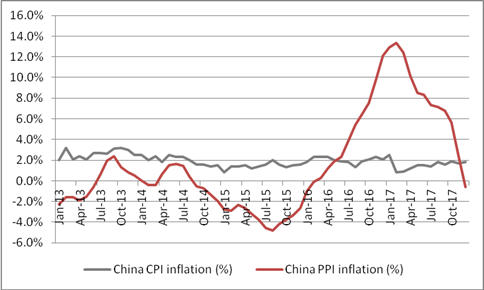

“Inflation. Capacity cuts in basic industries such as steel and mining mean producer prices (PPI) have risen fairly sharply, even if the consumer price index (CPI) has been subdued. Markets will not want to see China export too much inflation any more than they will want to see it export deflation in the wake of any devaluation.

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream

“The Chinese bond market. Like its Western equivalents this may well take its cue from inflation. And like its Western equivalents, the market for traded sovereign loans in China has seen prices slowly fall and yields slowly rise, as global markets have priced in this long-awaited global synchronised recovery (if that is what it is). Yields rising quickly could mean the economy is running too hot but falling yields could mean it is running too cold – so investors will be hoping to see something from the middle ground from the Middle Kingdom.”

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream