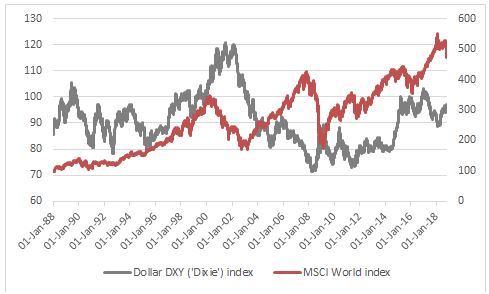

“The US dollar trades at an 18-month high, according a reading of 97 on the DXY (or ‘Dixie’) basket index. Whether this is the result of strong American economic fundamentals or weak British and European ones may be a matter for debate,” says Russ Mould, AJ Bell investment director. “But even if the dollar is benefiting from simply being the least dirty shirt, as it were, the buck’s potential to influence financial markets and thus investors’ portfolios should not be underestimated.”

“The big question now is whether this represents the next leg up in the dollar bull-run that began back in 2011.

“An 18-month high may sound impressive but a reading of 97 on the Dixie index is nothing compared to the peak reached in the two prior dollar advances witnessed since President Richard M. Nixon took America off the gold standard and smashed up the Bretton Woods monetary system in 1971.

“The dollar index peaked at 164.1 in February 1985 (a surge which forced the G5 – as it was then - to agree to devalue the dollar under the Plaza Accord, via a series of currency market interventions) and 120.2 in February 2002.

“If the buck really gets going, it could therefore have a lot further to run, with potential implications for global markets – and especially emerging market ones – as well as commodity prices.

Source: Refinitiv data

The potential impact of a strong dollar

Global markets

“Global stocks eventually came a cropper after a period of sustained dollar gains in 2000, thrived on the weakness of 2002-07 and then plunged again as the buck briefly soared in 2007-09. All of this makes the broad stock market advances forged this decade appear like an interesting outlier, although a rising dollar did not immediately interfere with the bull market of the late 1990s.

Source: Refinitiv data

Emerging markets

“Emerging stock markets have been particularly sensitive in the past to the greenback, falling when the buck bounces and gaining when it rolls over. Dollar strength preceded the 1982 Mexican debt crisis, 1994’s so-called ‘Tequila crisis,’ also in Mexico, the Asia and Russian debt and currency collapses of 1997-98 and also heralded a period of deep Emerging Market (EM) equity underperformance relative to developed arenas in the first half of this decade.

“This year’s weakness in the Turkish lira, Argentinean peso, Brazilian real, Indonesian Rupiah and Indian rupee means that the currencies of five of the world’s 25 biggest economies shows the pressure that a strong dollar can put on EM economies.

“A strong dollar makes it more expensive for non-dollar nations and companies to service any debts they have that are denominated in the US currency.

“According to data from the Bank of International Settlements, emerging markets represent one-third of all non-bank borrowing outside the USA that is priced in dollars, with liabilities of nearly $4 trillion.

“It won’t take a big fall in their own currencies against the American one to make servicing those debts much more expensive, to the potential detriment of Government and corporate cash flow, and thus economic growth, since interest payments will take precedence over investment.

Commodities

“Commodities have also tended to do better during periods of dollar weakness and less well during periods of greenback gains. The theory here is that a strong greenback makes dollar-priced raw materials more expensive for those nations whose currencies are not linked to the buck, although this is not currently holding back the oil price, for example.

“Investors – and especially those with exposure to emerging markets – may therefore need to bear in mind American politician and one-time Treasury Secretary John Connally’s remark to his country’s trading partners (and rivals) that ‘The dollar is our currency, but it’s your problem.’”