• The Bank of England is expected to keep rates on hold when it meets on Thursday, despite inflation rising from 0.7% to 2.5% so far this year

• Going forward big rises in the oil price and wages should drop out of the equation, and tax rises are on the horizon, all of which will serve to dampen inflation

• While arguments for and against inflation are finely balanced, the Bank of England has plenty of firepower to deal with inflation, but it’s almost out of ammo when it comes to propping up the economy

• Investors are not in the same position - inflationary risks are real and portfolios are likely to be skewed towards assets that have swelled in value in a low inflation environment

Laith Khalaf, head of investment analysis at AJ Bell, comments:

“Inflation is on the rise, but the jury is out on how sustained price rises will be, as there are compelling arguments on both sides of the inflationary divide. Huge amounts of fiscal and monetary stimulus stand a good chance of coaxing the inflationary genie out of the bottle, but at the same time there are seemingly valid reasons why the Bank of England is holding off hiking rates, in the belief that inflation is transitory.

“Economic distortions that occurred last year will gradually fall out of the picture, which should have a moderating effect on the headline inflation rate. In particular, rising fuel costs and high wage growth don’t look repeatable year on year. We should also be mindful that the Chancellor’s stimulative giveaways in the March Budget were also accompanied by a tax grab starting in 2023, taking money out of the pockets of consumers and businesses to balance the books, and hence acting as a brake on inflation.

“Probably the clincher for the central bank is the highly asymmetric nature of its firepower. With interest rates at historic lows, and £895 billion of QE on the books, the Bank has plenty of ammunition to fight inflation if required. If it needs to stimulate the economy on the other hand, it’s got hardly anything left in the locker. For the Bank of England, it therefore makes sense to err on the side of stoking inflation rather than risk undermining the economy.

“Inflation poses a different puzzle to investors than it does the central bank though. Many of the assets that have swelled in portfolios over the last decade have been those that prosper in a low inflation environment, and conversely will struggle if price rises take hold. Investment portfolios are therefore likely to be underprepared for an inflationary environment without some adjustment, and if the weight of evidence starts tipping towards sustained price rises, investors may rue not having rebalanced their investments.”

Why the Bank of England is looking through inflation

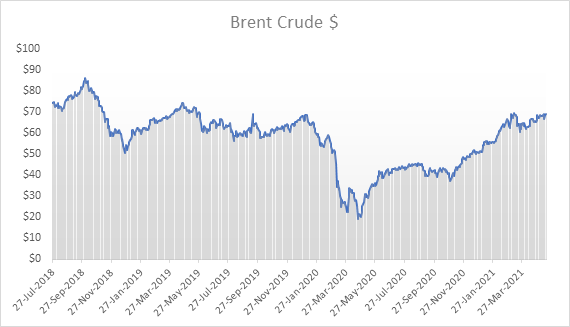

Oil prices

The oil price is a key component of inflation, but if we look at the oil price today, it is little changed from two years ago. Compared to one year ago however, it is significantly higher because of the huge fall in fuel demand following global lockdowns last spring and summer. Indeed at one point some oil contracts started trading at negative prices, so distressed was the market. Headline inflation is an annual figure, comparing prices today with prices one year ago. It’s therefore not just a picture of what is happening today, but how that compares to what was happening last year. In order to continue to exert a similar upward force on inflation over the coming year, we would need to see another dramatic rise in the oil price, and it seems highly unlikely we will see a demand or supply shock as significant as the mothballing of major economies which we witnessed in 2020.

Source: Refinitiv

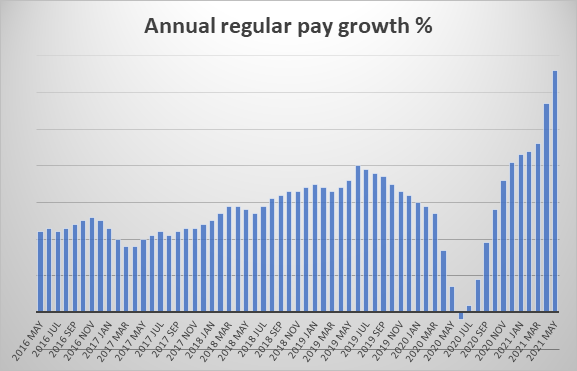

Wages

Wage growth is also a key plank of inflationary fears, and is currently running hot at around 6.6% at the last ONS reading in May. Again though, this annual figure is distorted by the pandemic effects on the labour market. Many of the jobs lost during the pandemic were lower paid roles in the hospitality sector, which has skewed the arithmetic of average wages upwards. As these roles return to the workforce, this should act as a brake on average wage growth going forward. Furlough has also played a big part in stoking wage inflation. Last May, 8.4 million workers were on furlough, according to government figures, compared to 2.4 million this May. That’s an awful lot of people going from receiving 80% of their salary to 100%, and that clearly exerts upward pressure on annual wage growth figures, yet it’s not a gain we can expect to be repeated year on year.

Source: ONS

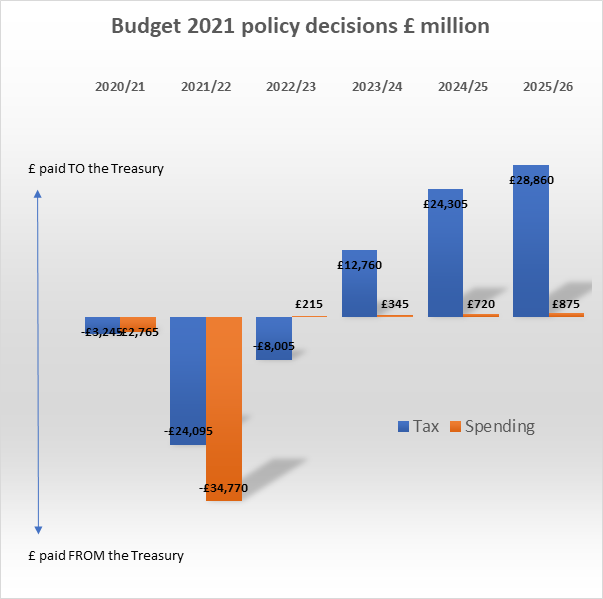

Fiscal policy

The Treasury is currently pumping lots of money into the economy to prop it up in the face of the pandemic, but the hand that giveth will become the hand that taketh away. In the short term, policies like the furlough scheme, business rates relief, and the super deduction for capital expenditure are costing the Exchequer huge sums of money. That money is going into the hands of consumers and businesses, enabling them to buy more goods and services, potentially adding to an inflationary spiral. But from 2023 onwards, the government is clawing large amounts back from businesses and consumers, mainly through freezing tax allowances, and raising corporation tax. By withdrawing money from the economy to balance the books from 2023 onwards, fiscal policy should start acting as a brake on inflation, rather than adding fuel to the fire.

Source: HM Treasury

Central bank firepower

With bank rate so low, the central bank has lots of potential to fight off inflation with interest rate rises, or by withdrawing QE. That would inflict pain on mortgage borrowers and businesses with large debts to service, however the toolkit is there to deal with rising prices. On the other hand, the Bank doesn’t have much room to manoeuvre by cutting interest rates in the event of an economic downturn, so that means the bank will likely err on the side of stoking inflation, rather than risking undermining economic growth.

The case for inflation

While the factors outlined above should help to contain inflation, there are also forces pushing in the opposite direction. Fiscal and monetary stimulus are currently abundant, and if combined with a synchronised global economic recovery from the pandemic, could sow the seeds for an inflationary period. The fact that central banks are willing to look through rising prices also adds to the risks, as if sustained inflation is taking hold right before our eyes, rate setters will be late in taking action to deal with it.

Investors therefore shouldn’t be complacent about inflation, and their portfolios may well be skewed towards investments which won’t perform well in an inflationary period. The low interest rate environment we’ve seen in the last decade or so has led to a ballooning in the value of assets that thrive in a low inflation environment, and conversely might struggle if inflation takes off. Chief amongst these are long dated government bonds, and also investments that can act as bond proxies, such as reliable, high quality, blue chip companies. The benign inflationary environment has also created the perfect conditions for growth stocks, particularly in the tech sector, where the appeal of foregoing profits today in favour of profits tomorrow is not heavily eroded by high rates of inflation while you wait. These investments may well still warrant a place in pensions and ISAs, but their strong performance means they may now make up an outsized proportion of portfolios, which potentially leaves investors at risk from an inflationary shock. Some reallocation of profits may therefore be in order. So far, the case for and against inflation is finely balanced, and that suggests investor portfolios should be too.