“The combination of a pandemic, recession and supply-side destruction on one side, and massive monetary stimulus, fiscal stimulus and changes in working and consumption patterns on the other means that no-one knows what’s coming next – not even central bankers. If they did, they would hardly still be running policies that were described as emergency measures when they were launched in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis,” says AJ Bell Investment Director Russ Mould. “Possible outcomes include an inflationary boom, a deflationary slump or a stagflationary swamp and the hard part for investors is that each scenario potentially requires a different portfolio solution and asset allocation strategy, at least if history is any guide.

“It is easy to make a compelling case for any one of those three scenarios:

• Inflation could result from onshoring (as this will mean more expensive, Western labour); soaring energy prices as supply of hydrocarbons is restrained to meet zero-carbon targets even as demand grows; and monetary and fiscal stimulus that are boosting overall demand for goods and services even as supply chains remain brittle, even fractured.

• Deflation, or disinflation, could yet result as technology continues to drive productivity and automation reduces the need for staff and workers; as the erosion of the power of trades unions keeps a lid on wage demands; and supply-side bottlenecks and temporary dislocations in supply start to ease.

• Stagflation, perhaps the worst of all worlds, could yet result owing to global debt levels, which stand at record highs and where interest payments suck cash away from other, more productive investment and hold back growth; where Quantitative Easing and Zero Interest Rate Policies keep alive ‘zombie’ firms which are hogging capital that could perhaps be allocated more effectively elsewhere; and demand starts to stagnate after an initial post-pandemic boom, not least because consumers and corporations have to service the extra debt taken on to see them through the viral outbreak and central banks and Governments will, surely, eventually begin to offer less stimulus.

|

SCENARIO |

INFLATION |

DEFLATION |

STAGFLATION |

|

Case for |

Onshoring |

Demise of unions |

Debt |

|

|

Energy supply restraint |

Tech and productivity |

QE and zombie firms |

|

|

Fiscal and monetary stimulus |

Easing of bottlenecks |

Stagnant demand |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Precedents |

UK early 1970s |

UK, USA, 1930s |

UK late 1970s |

|

|

US 1970s |

Japan since 1990 |

|

|

|

Emerging markets 2010s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Portfolio winners* |

‘Real’ assets |

‘Paper’ assets |

Gold |

|

|

Short-duration assets |

Long-duration assets |

Pricing power |

|

|

Value / cyclicals (jam today) |

Technology (jam tomorrow) |

Asset-light |

|

|

Commodities |

Bonds |

|

|

|

Property |

Cash |

|

|

|

Index-linkers |

|

|

*Based on past performance only. The past is no guarantee for the future

“There are precedents for all three and investors can look back on those episodes for guidance as to which asset classes did best then – albeit in the knowledge that the past is no guarantee for the future. If it were, as Warren Buffett once noted tartly, ‘If past history is all there was to the game, the richest people would be librarians.’

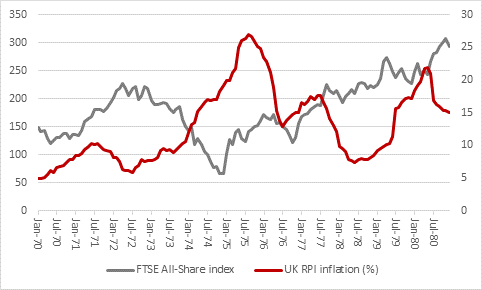

• Inflation has in the past seen ‘real’ assets (or paper claims on them) outperform. After all, Governments can print money but they cannot print oil, gold or property, to paraphrase Warren Buffett, and those ‘real’ assets may therefore offer some degree of wealth preservation in the face of rampant money creation. Index-linked bonds may offer some protection and investors may also be tempted to gravitate toward cyclicals. In inflation is running hot, then nominal GDP will look good, so will nominal sales and (possibly) profits. In that case, investors will be able to buy earnings and cash flow growth now – jam today – and do so at firms that have underperformed and potentially cheap (in contrast to the long-term growth stocks which have done so well for so long, offering jam tomorrow at much higher multiples as a result).

The caveat here is that UK equities started their post crack-up boom recovery in the mid-1970s after a crushing bear market which left stocks trading on an average of barely five times forward earnings (and that bear market was at least partly caused by the first of no fewer than four waves of inflation which swept over the nation in the 1970s). The UK now trades on an earnings multiple in the mid-teens and the USA in the low-20s, so the starting points are very different on this occasion.

Source: Refinitiv data, ONS

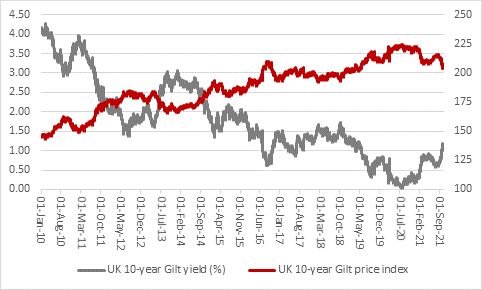

• Deflation, or at least disinflation, would lean towards cash and bonds, uncomfortable as that may sound, especially given where yields are right now. If prices start falling, even those modest (or even negative nominal) returns would look appealing, given the capital preservation they would offer. Plus, in the case of deflation, the odds on central banks returning to aggressive QE and NIRP policies must be good, creating a price insensitive buyer for fixed-income instruments, especially Government bonds.

Source: Refinitiv data

A repeat of the last 10 years’ low-growth, low-inflation, low-rates environment could also lead investors to stick with another asset class that has worked so well for the last decade, namely growth stocks, such as tech, biotech and social media. These firms are seen as capable of generating earnings growth almost regardless of the economic conditions and as such are highly prized and enjoy premium valuations as a result.

The caveat is that it is unusual for the globe to remain in a steady state for too long -change is the only constant. It is tempting to extrapolate our most recent experiences and base our future expectations upon them but from an investment point of view this often leads to trouble. Anyone who bought Japan in 1990 (after a decade of stunning performance), tech media and telecoms in 2000 (after a decade of stunning outperformance) and China and mining stocks in 2010 (after a decade of stunning performance) would have suffered terrible returns for the next decade (and more).

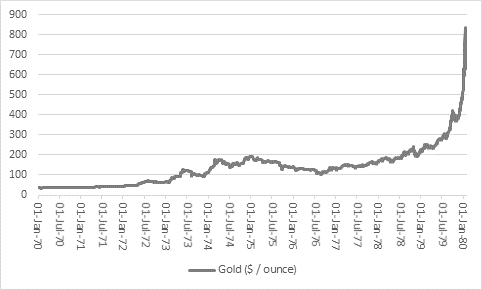

• Stagflation is much the rarest scenario and we really only have the 1970s to lean upon. It is possible to argue that there are clear parallels between then and now – Governments scrabbling to find money for welfare programmes, easy money in the form of fiscal stimulus, a potential energy shock and heightened geopolitical tensions – with the result that we could yet have to face the worst of both worlds: limited or negative GDP growth and sticky or rising prices.

In the 1970s, gold was the best performing asset by a mile, as it surged from $35 an ounce to a peak above $800. The caveat here could be that we are starting off at $1,800 an ounce this time around.

Source: Refinitiv data

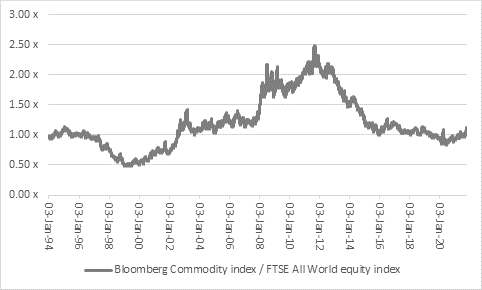

“No-one knows what is coming. But we do know what markets are pricing in, because equities (‘paper assets’) have outperformed commodities (‘real assets’) hands down for a decade, with growth and tech stocks leading the way. That implies markets still have faith in central banks, see the current inflationary spike as transitory and believe the formula for the last decade will remain the same in the next one. The gradual resurgence of commodities relative to equities must therefore be watched, as this suggests doubts are starting to appear.

Source: Refinitiv data

“That could come to pass. But if nothing else, investors know that any deviation from that path, in the form of inflation or stagflation, could cause volatility and see different asset classes come to the fore.

“A portfolio that prepares for all three scenarios via diversified asset allocation might a plan to consider, complete with some cash for downside protection and scope to buy amid any wider shakedown, even if the investor may then choose to tilt that allocation to the scenario they feel is most likely.”