“Alphawave IP’s shares are already down by 20% on the first day of conditional dealings and the cynics will be queueing up to say it is no shock that a company with the stock ticker of AWE is coming a cropper, given its lofty price tag,” says AJ Bell Investment Director, Russ Mould. “This is a great shame, though, and no cause for celebration. Alphawave IP has a business model which investors understand and know can work well, thanks to the ARM Holdings’ time as a FTSE 100 firm, so London still seems like a good choice for the listing. But another poor start for a high profile flotation, and one that comes so soon after Deliveroo, will inevitably be used as a stick with which to beat the London Stock Exchange and the London market more widely, amid accusations that the UK investment community doesn’t ‘get’ technology or like entrepreneurs – when nothing could be further from the truth.

“The finger-pointing will now doubtless begin, as the company, advisers, investors and onlookers try to work out why Alphawave IP’s shares are sinking quite so fast, even though the global semiconductor industry seems to be booming right now and the company has a business model which looks perfect to capitalise upon demand for silicon chips over the long term as well.

“As it turns out, through sheer bad luck, Alphawave IP is coming to market in a volatile week. Global markets are suffering their first stumble for some time, owing to unrest in the Middle East, fears of inflation and ongoing concerns over what could be an uneven global recovery in light of India’s ongoing woes and outbreaks of COVID-19 in Taiwan.

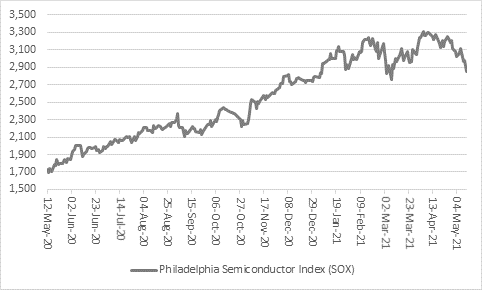

“Markets also seem to be turning slightly against long-term growth stories which offer ‘jam tomorrow’ in favour of cyclical recovery plays which have scope to offer rapid earnings increases now and therefore ‘jam today’. Tech stocks have started to slide and momentum favourites like Tesla, the ARK family of investment funds, SPACs and IPOs have all started to perform less well. Even the Philadelphia Semiconductor index, or SOX, has lost 14% OF its value since it peaked on 5 April, despite plentiful evidence that silicon chips are still in short supply.

Source: Refinitiv data

“In addition, Alphawave IP did come with a lofty valuation, so perhaps the company and its advisers need to assess whether they asked for too much, especially given current market conditions.

“The 410p offer price put a £3.1 billion price tag on the company – hardly a knock-down sum for a firm which, according to the prospectus, generated $44 million in sales, $24 million of operating profit and generated $15 million in cash from operations. Granted, Alphawave IP is growing very quickly, but such a valuation prices in a lot of future growth already and does so at a time, again, when investors may be able to buy plenty of cyclical, immediate growth cheaply if we do get a strong, post-pandemic upturn, with the result that they may not feel such a need to pay premium valuations for long-term secular growth well out into the future.

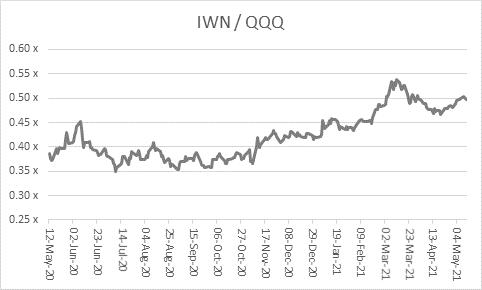

“Cyclical, jam-today growth – or ‘value’ for want of a better turn of phrase – has been outperforming sectors like tech and biotech – or ‘growth’ to use another clumsy tag – since last summer.

“This can be seen by comparing the price of two US-traded tracker funds, the iShares Russell 2000 ETF with that of the Invesco QQQ Trust.

“The former, with the ticker IWN, has nearly $17 billion of assets under management and follows a basket of 1,500 stocks that offer ‘value’ characteristics. Nearly three-quarters of the portfolio lies in the financials, industrials, consumer discretionary and real estate sectors – against barely 20% in the QQQ – and it has just 5% in technology, against 48% in the QQQ.

“The latter, with the ticker QQQ, is designed to track the performance of the NASDAQ Composite’s index’s largest 100 non-financial companies and deliver that performance to investors, minus its running costs. The QQQ has $164 billion in assets under administration and its biggest holdings are Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, Tesla, Facebook and NVIDIA. It is therefore a good proxy for ‘growth’ and those firms whose business models have thrived during the pandemic.

“Since last summer, IWN has been doing far better than QQQ, despite all of the attention which is still lavished upon big tech and despite the help those firms have offered to many during the pandemic.

Source: Refinitiv data

“The company’s advisers should have been aware of this trend and pitched the Alphawave IP’s IPO valuation accordingly, although it is possible that they tried and management elected not to listen.

“Valuing IPOs is a fine art and there is no right or wrong answer. The aim is to ultimately set a price that satisfies sellers and buyers and provides a good base for a healthy market once trading healthy, while a third interested party, the advisers, will also want to ensure they bag their fees.”

APPENDIX: Different types of semiconductor companies explained

• Chip-design software. These companies do not actually have silicon chip products of their own. Instead they sell electronic design automation (EDA) software tools, which help semiconductor companies configure new chip products more quickly. The global leaders in the field include US firms such as Cadence and Synopsis.

• Raw materials. One example here is AIM-quoted IQE which prepares the discs, or wafers, from which chips are manufactured. In IQE’s case, it provides specialist epitaxial wafers made of gallium arsenide (GaAs), gallium nitride (GaN) and indium phosphide (InP) which are used in specific markers such as markets such as mobile telecommunications and networking, rather than classic, mainstream pure silicon wafers.

• Fabless & chipless. Cambridge-based ARM is the daddy here, but this is how Alphawave IP operates, too. It does not make chips does not even have a chip design. Instead Alphawave IP licenses out an idea, or architecture, which chip companies can then use as the basis for their own designs and products and all three are therefore known as semiconductor intellectual property ('Semi IP') companies. The firm earns licence fees and also bags a royalty fee for each chip sold which is based on their architecture. This business model can be tremendously profit and cash generative, especially once royalty volumes reach a certain scale, as those revenues drop straight through to the bottom line. ARM was acquired by Japan’s Softbank in 2017 and is now the subject of a bid from America’s NVIDIA. Imagination Technologies was another example of a UK-based Semi IP firm. It was acquired in 2017 by Canyon Bridge, albeit only after its IP architectures were dropped by Apple, a major customer, so this operating model is by no means totally impervious to shocks, even if it does help to shelter players in this field from the worst of swings in the wider semiconductor industry cycle.

• Fabless. CML Microsystems designs and sells its own products, but it does not make them (and this was also the case with Wolfson and CSR, formerly UK-listed firms that were ultimately acquired). The manufacturing process is outsourced to a so-called silicon chip foundry (an area where Taiwan dominates, via TSMC and UMC, both of which are quoted on the Taipei stock exchange and have secondary listings in the USA). Fabless companies receive their income in the form of royalties, which are generated when a product featuring one of their chip designs is manufactured and sold. This model is very profitable if end volumes are strong but can run into problems when chip manufacturing capacity is tight, as the subcontractors can charge more for the manufacturing process, eating into the fabless firms' profits.

• Integrated. These firms design, sell and also manufacture their own chips. They are therefore highly operationally geared and will make extremely high margins when its factories are fully utilised, but can quickly plunge into loss if demand starts to waver and the production lines are not kept very busy. There are no real examples of this left on the UK market, but world leaders in this sphere include American microprocessor giant Intel Franco-Italian combine STMicroelectronics, Germany’s Infineon and Korean tech behemoth Samsung Electronics, whose prowess in the field of memory chips is unquestionable.

• Chip-making equipment. Chipmakers need to pack their factories with so-called semiconductor manufacturing equipment (SPE), kit which is used in the multi-stage process of manufacturing their products. When the semiconductor cycle is strong, chipmakers will build more factories, and order more equipment, to help them meet demand, but in a downturn, capital expenditure budgets are pared back to the minimum and orders postponed or cancelled. The UK is a bit bereft of listed pure SPE plays although precision instrument experts Spectris, Renishaw and Gooch & Housego are sub-suppliers of key components to SPE companies, where global leaders include the Netherlands' ASM Lithography, America's Applied Materials, LAM Research and KLA-Tencor, as well as Japan's Tokyo Electron and Advantest.